THE ART OF BECOMING

It’s around 10:35am as I get off the Dalston Lane Station bus stop. I’m already late, which has been a persistent issue since living in London. Coming from a city where the main centre is a ten minute bus ride, long, tedious commutes are foreign to me. The heat is oppressive, but the gentle zephyr that glosses over my skin grants me the long needed coolness I craved. As I arrive, the Hackney Archives and Dalston C.L.R James Library is saturated in a radiant, lethargic glow, with fragments of light dancing on the glass-paned facade.

Behind the contemporary exterior, this archive space conceals a tumultuous history. Since the late 19th century, this building has been opened as a circus hippodrome, converted as a cinema, briefly used as a warehouse and car showroom, been a landmark venue for Reggae, Roots, Soul and R&B and a nightclub, before the new Dalston C.L.R. James Library with Hackney Archives opened on the site in 2012.¹ The building holds the library on the first two floors and the archive space on the third floor. On entering the archive space, I became mesmerised by the ethereal rays of sunlight that pushed through the colossal windows, presenting an illusion of infinite space, done meticulously and elegantly, rather like some of the interior paintings of Johannes Vermeers where sunlight is central to the oil painting and advances onto the subjects with an implacable air.

The archive has an unyielding determination to preserve Hackney’s rich and heterogeneous history, making local history accessible to the public and stimulating community engagement with its materials. It also offers opportunities for locals to contribute to the archive’s flourishing collection. With over 600 years of Hackney’s history, the archive holds over 17,000 historic photos, maps dating back to the 1700s, local newspapers, books on various subjects, street directories, Abney Park Cemetery records on microfilm, electoral registers and free access to Ancestry Library Edition.² It’s a prodigious collection, paying homage to the eclectic souls, musings and lives that have sauntered through the archaic streets of Hackney.

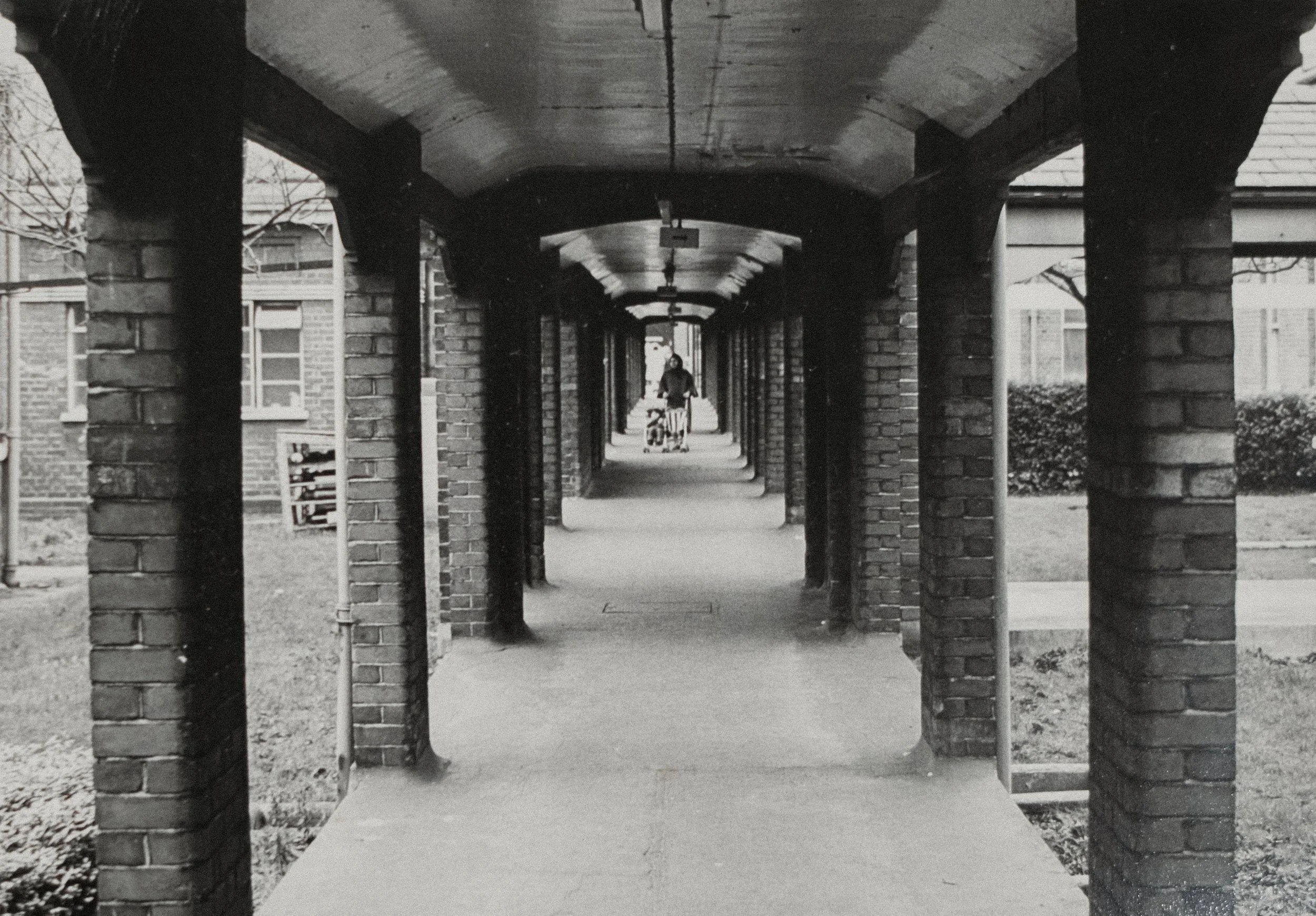

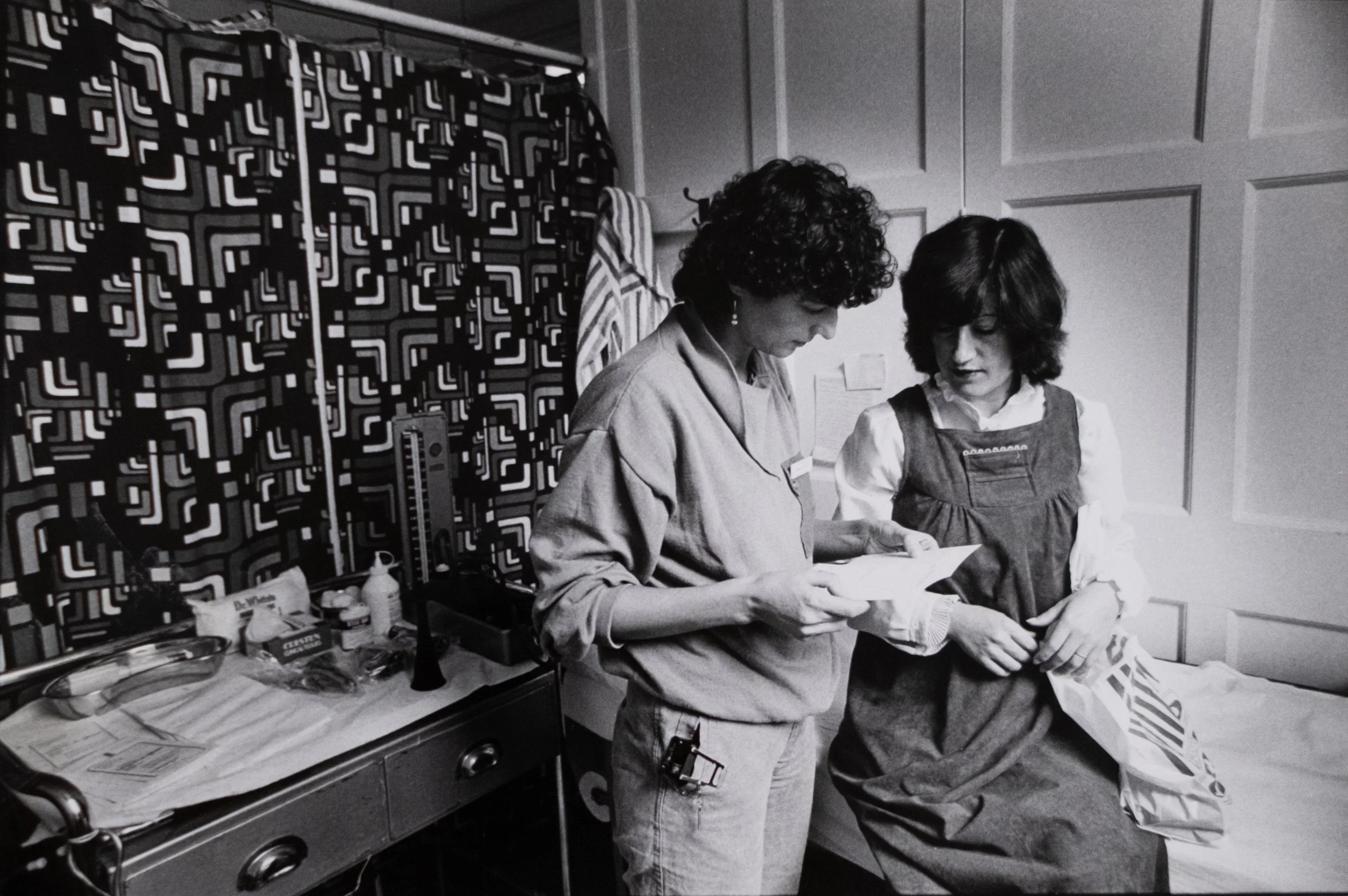

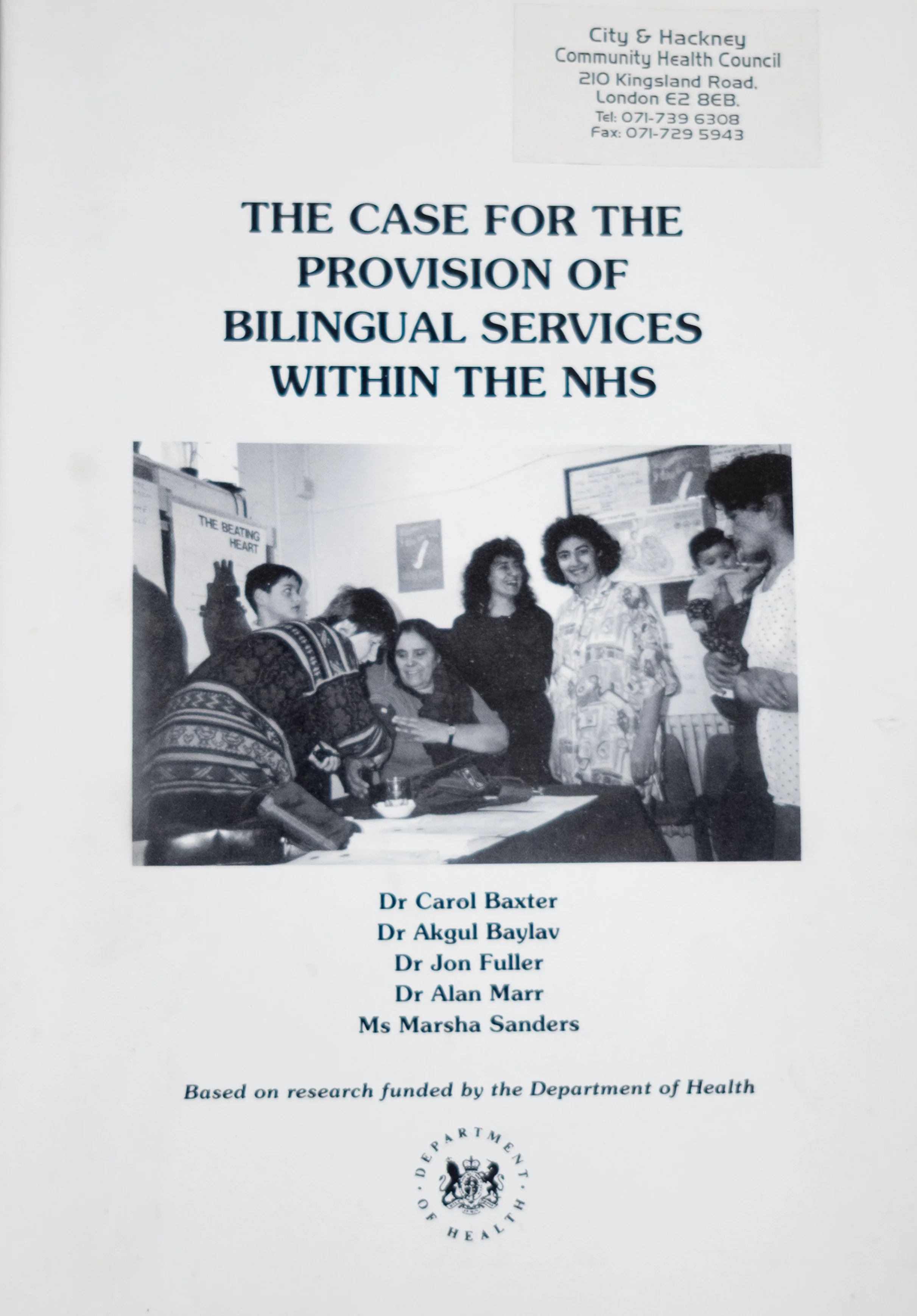

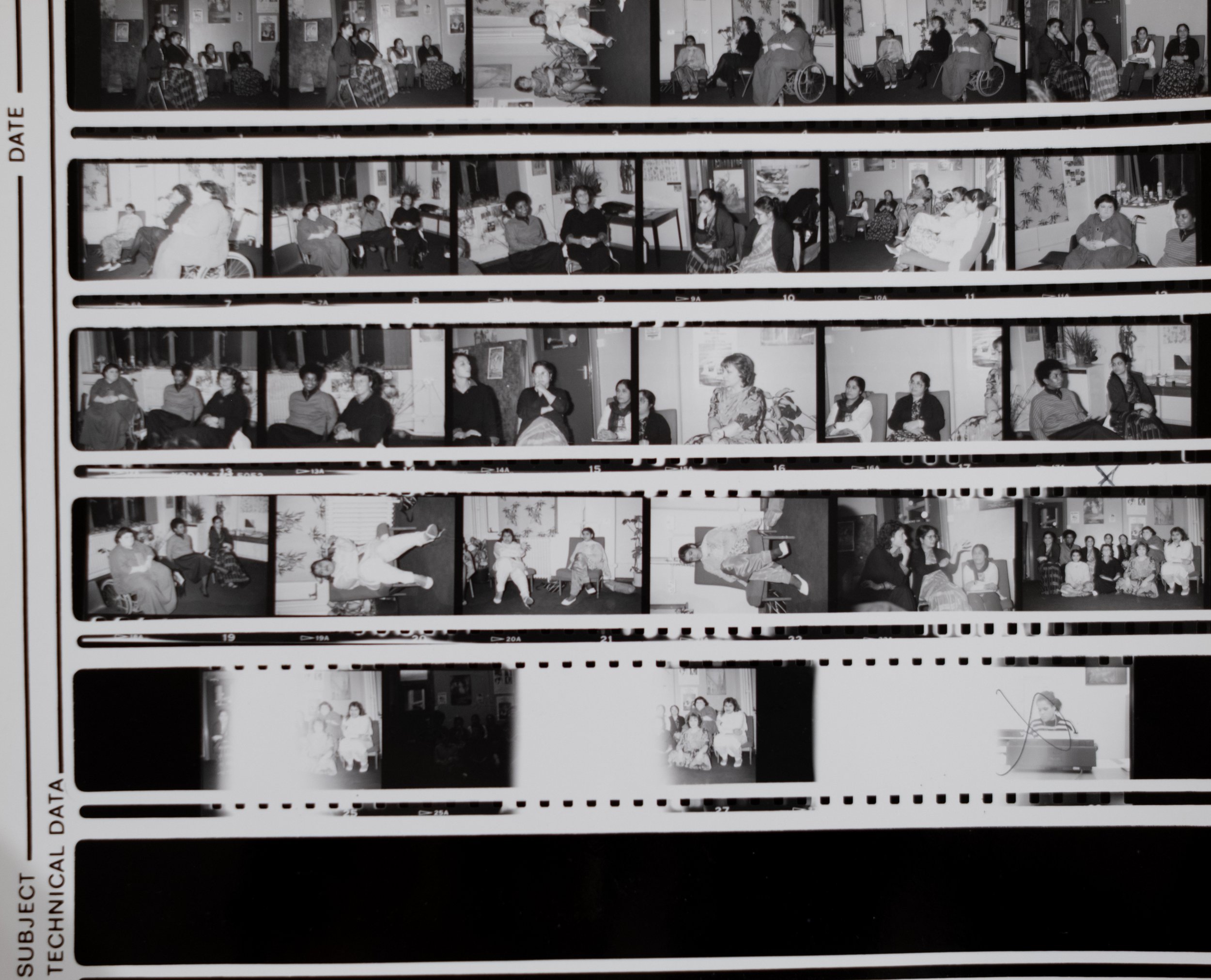

I completed my work placement at Hackney Archives, which was part of my Archives and Records Management MA course at UCL. I worked with a single collection comprising two distinct series: the Neave Brown series (1960s–1997) and the Multi Ethnic Women’s Health Project (MEWHP) series (1980s–2000s). The Neave Brown series consists of materials created by the eponymous British modernist architect, including seminar papers, architectural drawings, writings and photographs related to housing projects, urban planning and academic contributions. The MEWHP series documents efforts to improve healthcare access for non-English speaking women in Hackney, particularly for Bengali, Turkish, Urdu and Gujarati-speaking communities. It includes administrative records, policy documents, photographs, publications and materials on health advocacy.

My task involved understanding the scope of each collection, identifying any copyright or data protection concerns and completing the cataloguing template used by Hackney Archives. This process included organising detailed descriptions for each item, noting aspects like dates, creators, formats and subjects. Additionally, I conducted external research to uncover relevant historical context or connections that might enrich the collection’s description. As part of the cataloguing process, I was also responsible for ensuring proper preservation of the materials by packaging them according to archival standards. This involved using acid-free paper for delicate items and placing them in suitable archival boxes to ensure long-term preservation.

My first experience cataloguing was chaotic; my emotions ranged from disoriented, anxious, disheartened and frustrated. Yet, beneath all of this was a strong zeal, a bona fide passion to understand the records strewn before me.

My state of restlessness stemmed primarily from my preoccupation with perfectionism — a quality antithetical to the intrinsic nature of the archival world. Perfection suggests completion, yet archives are constantly in a state of becoming, of re-interpretation.³ Archives are not static collections but dynamic “systems of discursivity” that determine what can be known and remembered.⁴ Like other disciplines, archives are organised within a specific paradigm that chooses what discourses, information and events are preserved, and what is obscured, excluded or forgotten. Even if I were to ‘complete’ this collection in terms of how to logically present it to the public, what if new information arises in the future? How would this impact the ‘perfect’ structure I have pained to construct? The goal here was simply to create the beginning of this archive, to establish the fonds and to start the process of making these collections known and accessible.

There were an abundance of difficulties, yet finding the intellectual justification to keep or change the original order of the collection was the most paralysing. Of course, one must avoid intentionally changing the original order, as disrupting it would obscure provenance. Laura Millar explains the concept of provenance succinctly in her book Archives: Principles and Practices:

“In the archival context, provenance is defined as the origin or source of something, or as the person, agency or office of origin that created, acquired, used and retained a body of records in the course of their work or life. Archivists emphasize the importance of respecting the individual, family or organization that created or received the items that make up a unit of archival materials. In order to preserve the provenance of groups of archival material, the archivist does not put together archival materials from different creators nor reorganize groups of archives by subject, chronology, geographic division or other criteria. To do so would be to destroy the context in which the archival record came to be, diminishing the role of the creator and the relationships that person or agency had with other people or groups.”⁵

The issue arose because the donor had provided four boxes — three dedicated to the MEWHP and one pertaining to Neave Brown — without explaining the connection. At first, the rationalisation to change the original order seemed sensible, as the materials were unrelated in subject matter. But, as Millar notes, respecting the context in which the archival materials came in is paramount. The creator’s choices mustn't slip into obscurity. And thus, the lack of providential information shared by the donor began a long, agonising journey of mediation. What did these two groups of materials have to do with each other?

Unable to discern the relationship between the two, my mind subconsciously treated them as two separate collections. While I had no intention of keeping the records divided at the end of the process, treating them as separate entities in the beginning stages proved unproductive. It resulted in confusion during the cataloguing process and disrupted the logical flow of the materials. This experience reinforced the principle that respecting the integrity of the original collection is crucial, even when the materials appear disjointed or unrelated. Yet, this had me questioning the following — what is considered ‘logical’? If the purpose is to make sure that users understand the collection, why would the human tendency to make the order clearer be considered inappropriate? Based on this particular collection, the concept of ‘original order’ seemed all the more peculiar, as the boxes were evidently just papers and files curated for years, hurled into some boxes. “The usual archival hierarchical series structure,” Jennifer Douglas notes, “is often more an archival construct than it is an original order, since the archivist's inference of intellectual order is necessarily based on limited knowledge of original contexts and because the identification of intellectual order is inevitably influenced by how archivists understand the ideal structure of a fonds.”⁶ What is the ‘ideal structure of a fonds,’ who determines it and do archivists have the ethical right to impose it on collections they receive? I truly underestimated the intellectual rigour it takes to deal with respect de fonds. While the ISAD(G) standard promotes the retention of original order where possible, clearly applying this principle in practice was more convoluted than I had anticipated.⁷ Most recent standards have understood the extent of this complexity and have made attempts to address these issues.⁸ Thus, the balance between historical authenticity and user accessibility is not always clear. The decision to impose a clearer structure could have improved user experience, but it would have undermined the historical context of the collection. On the other hand, preserving the original order risked confusing future researchers. In these cases, there was rarely a definitive answer, and I had to rely on my judgment to make decisions that addressed both dimensions (an incredibly daunting task for a first-timer).

Nevertheless, my cataloguing experience at Hackney Archive equipped me with a well-needed introduction into the everyday realities of what it means to deal with records. It provided me with an acute realisation: theoretical archival standards and real-world institutional practices are worlds apart.

It was thus that during the first few weeks of summer, in the heat beneath the windowpanes at Hackney Archives, I felt, because of the collection I was exploring, homesick for a period in the past that I never experienced, where I would see Hafize communicating the needs of a Turkish woman to the midwife, and where, in the depth of the teeming hospital, unnerved Non-English speaking women were bewildered, clustered in the suffocating waiting rooms: not far off, in a lecture hall, I would listen to a talk by Neave Brown about the techniques of Le Corbusier, monopolised by the feelings of beguilement and magnetism that brews inside the soul of an ardent student who has too long been plagued by pedantic academic lecturers. And since this yearning for a life I never had was always vividly present in my mind, during those weeks of summer that homesickness was impregnated with the vigorous curiosity of a historian; and whichever non-English speaking woman I encountered, an amalgamation of empathy, pain, heartache and questions would arise immediately because, my God, how much has she had to endure? How much strange, ubiquitous stares have burdened her since arriving in this foreign land? The archives that I explored were for me not merely a unique aspect of Hackney’s history, but otherwise a microcosm of England. The veracious image of the forsaken immigrant woman, so largely ignored during this time of history — a fundamental part of England’s post-colonial narrative itself, worthy to be studied and explored.

¹ Hackney Council, Hackney Council ready to open brand new library in Dalston, 09 January 2012, Hackney Council News, Hackney Council. Available at: https://news.hackney.gov.uk/news/hackney-council-ready-to-open-brand-new-library-in-dalston (Accessed: 3 February 2026).

² Hackney Council, Archives collections, Hackney Archives, Hackney Council. Available at: https://hackney.gov.uk/archives-collections (Accessed: 3 February 2026).

³ Wendy M. Duff and Verne Harris, “Stories and Names: Archival Description as Narrating Records and Constructing Meanings,” Archival Science, 2 (2002), pp. 263–285, pp. 265–266.

⁴ Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge (London: Routledge, 2002), p. 145.

⁵ L.A. Millar, ‘Archival history and theory’, in Archives: Principles and Practices (London: Facet, 2017), pp. 37–66.

⁶ J. Douglas, ‘Toward more honest description’, The American Archivist, 79(1) (2016), pp. 26–55, p. 47. Available at: https://american-archivist.kglmeridian.com/view/journals/aarc/79/1/article-p26.xml (Accessed: 4 November 2025).

⁷ International Council on Archives, ISAD(G): General International Standard Archival Description, 2nd edn. (Ottawa: ICA, 2000), p. 13.

⁸ International Council on Archives, Records in Contexts (RiC) Conceptual Model, version 1.0 (Paris: ICA, 2024), p. 5. Available at: https://www.ica.org/en/records-in-contexts-conceptual-model (Accessed: 4 November 2025).