IN SEARCH OF MEMORIES

“Always try to keep a piece of sky over your life,” M. Legrandin would advise Marcel. “You have a lovely soul of a rare quality, an artist’s nature, don’t ever let it go without what it needs.”¹ Perhaps I, too, should take M. Legrandin’s advice. I have been scathed by the erratic maelstrom of passions that stir up inside my mind when I’ve been secluded for too long at home, much like the water that begins to rotate at a central point during a 鳴門の渦潮 (Naruto no Uzushio), where the varying pressures, speeds and directions force a powerful rotation beyond control. It is a visual entity that cannot be reasoned with, unsettling due to its pure chaos. Yet, it is easy to forget the temporality of these internal collisions – painful, yes, but inseparable from life in all its vicissitudes. Despite the fleeting irresolution, I left my house.

I took the bus numbered 36 towards Chilwell, getting off at University South Entrance (stop UN07), then walked through the arched gate towards the Lakeside Arts Centre, where the sweet crisp air and the mellifluous voices of birds gradually restored a sense of tranquillity within me. I found myself hoping that the physical sense of coldness would dissipate the numbness that settles in my soul whenever I retreat into the shadows of my bedroom, illuminated only by a computer screen, a Kindle or a desk lamp. My hope was actualised, for I started to feel a renewed yearning for Mother Nature’s quiet repose and her soul-cleansing effect. A few minutes wandering the gated rocky pathway were enough to remind me that life extended beyond the four walls of my bedroom.

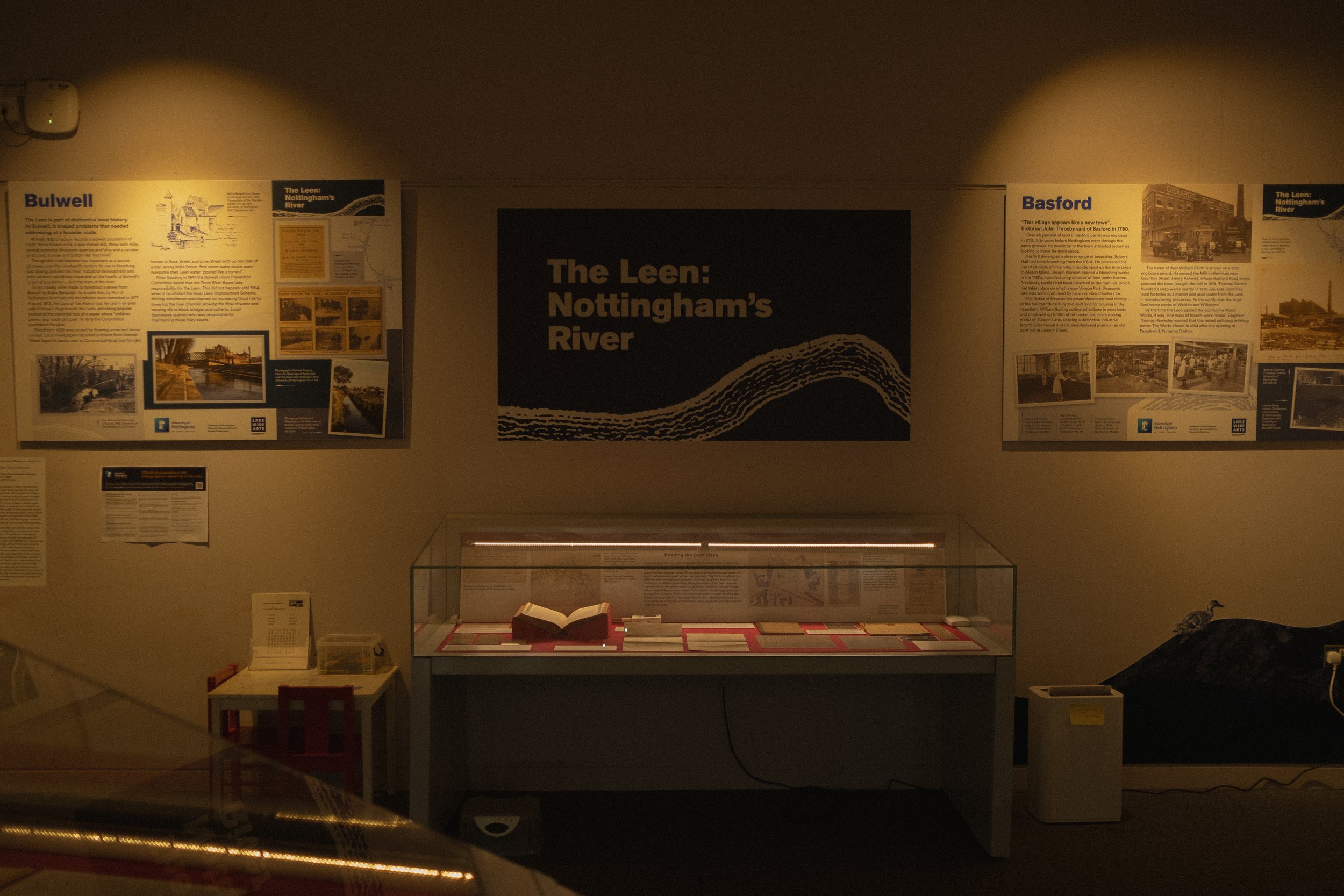

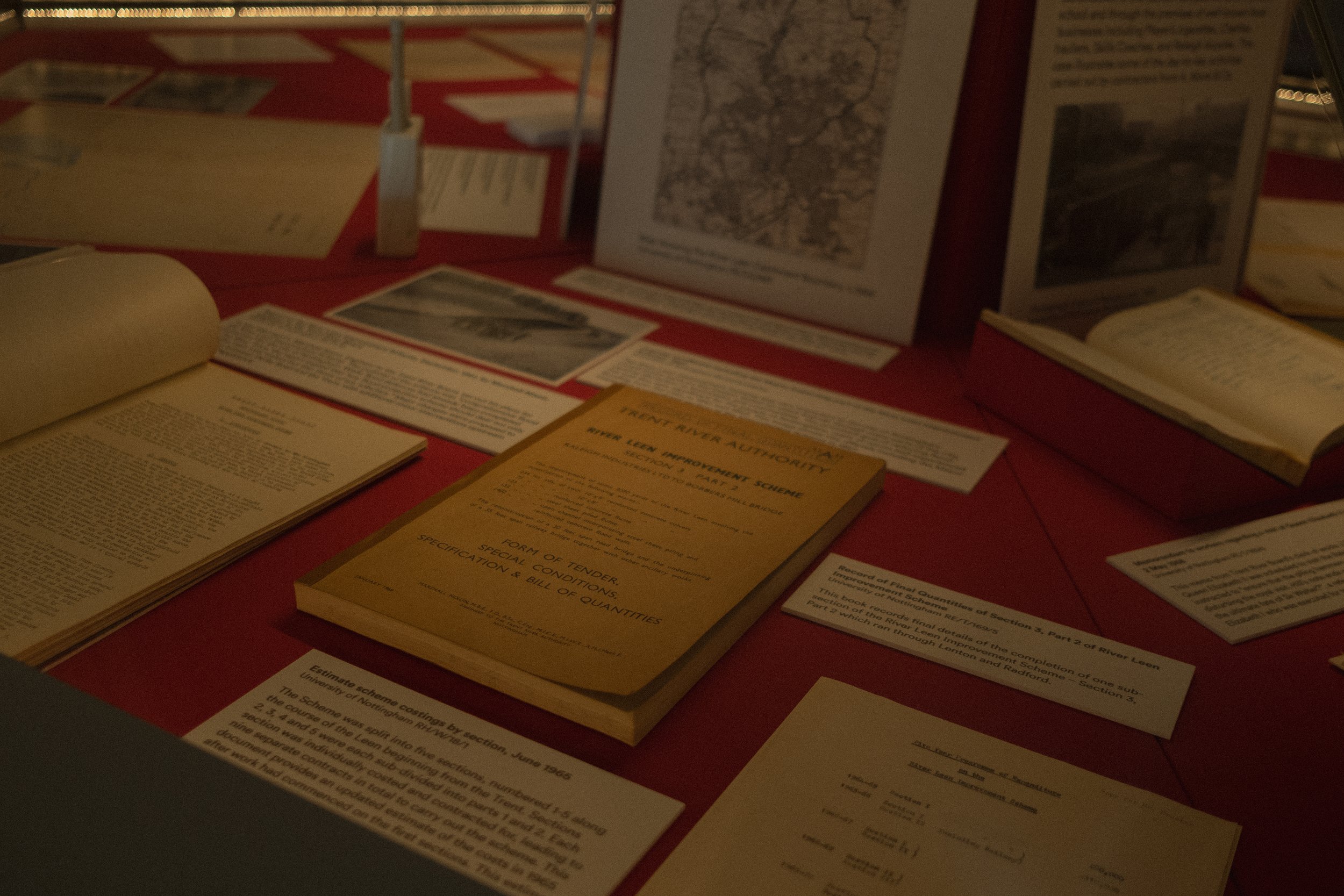

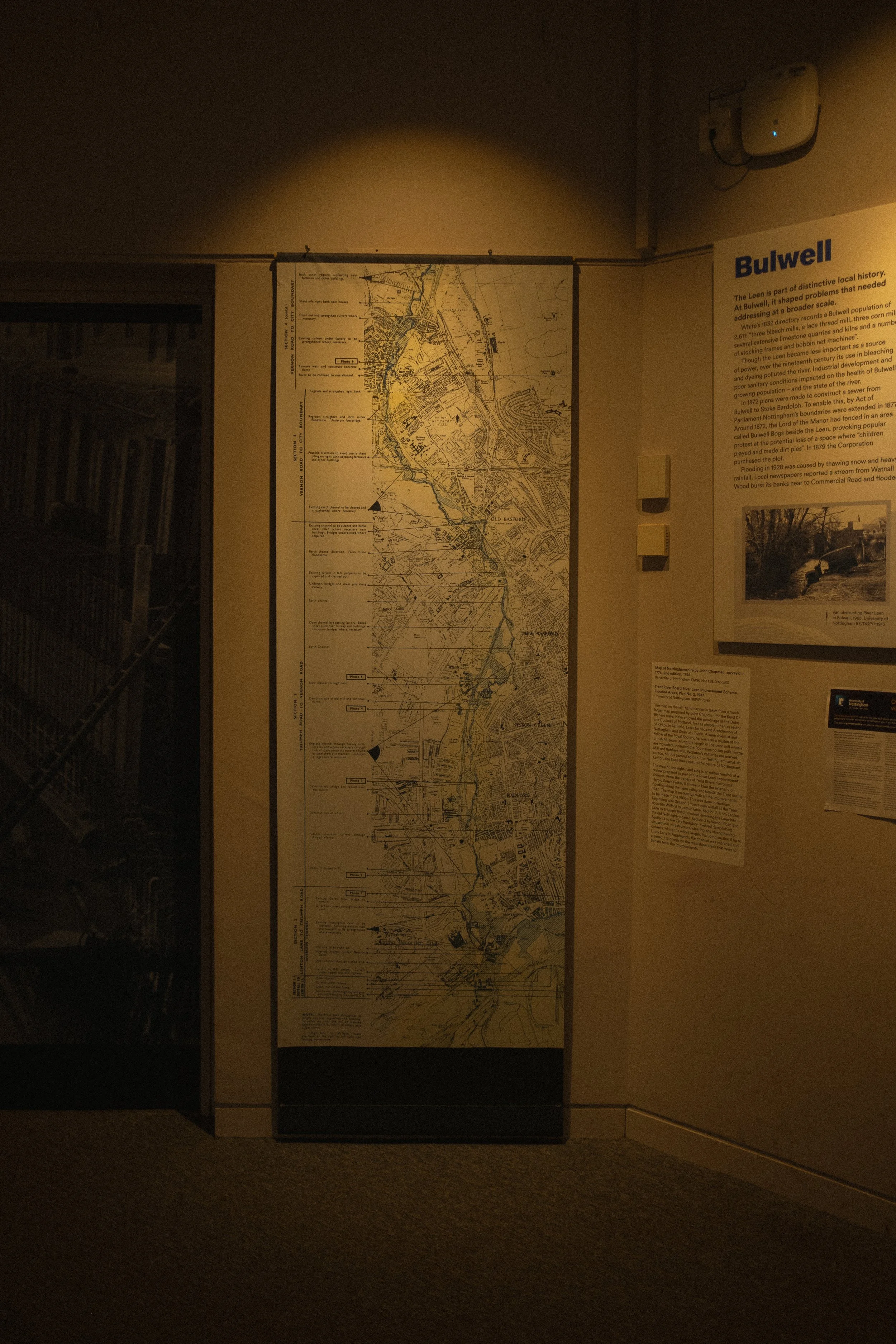

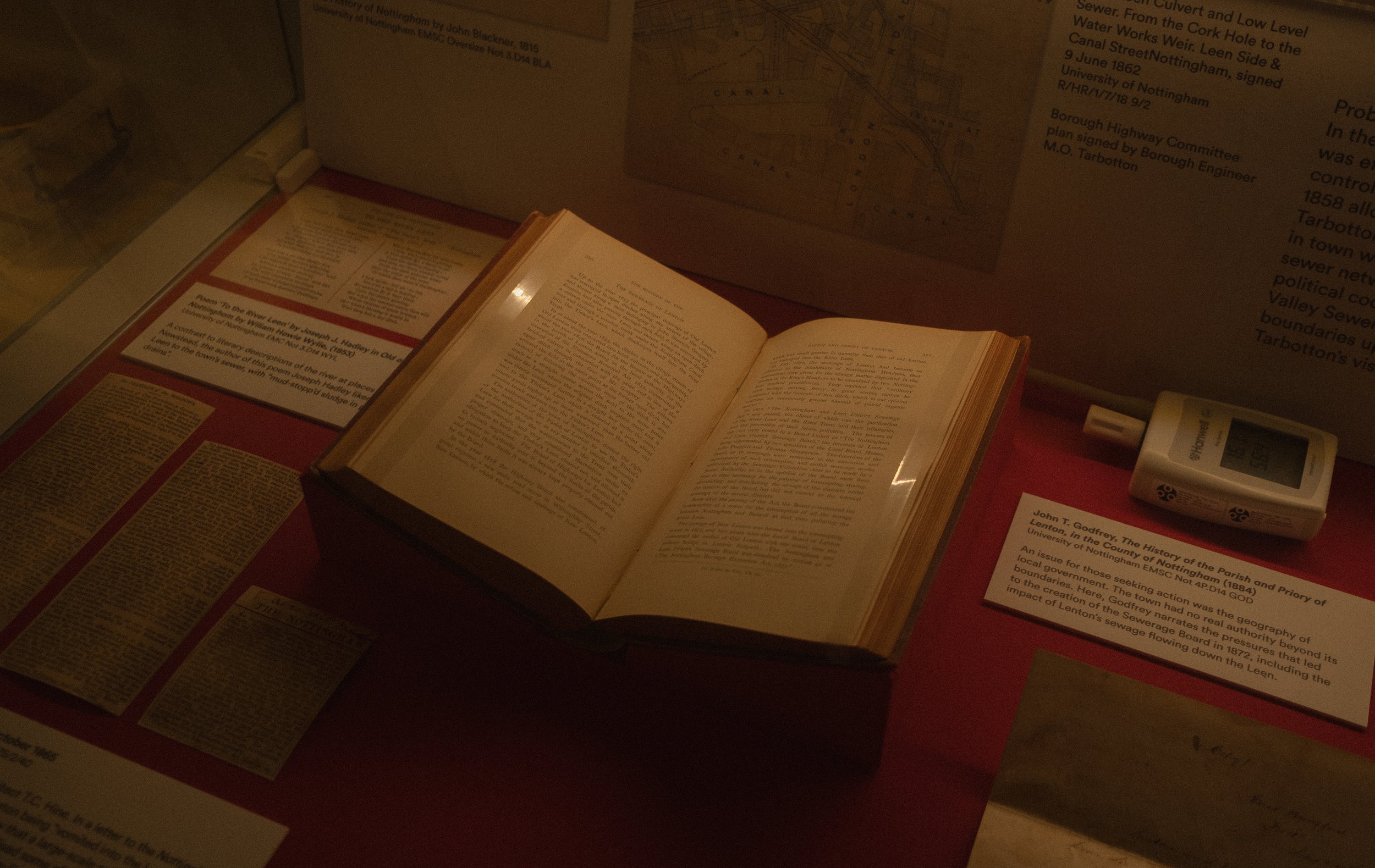

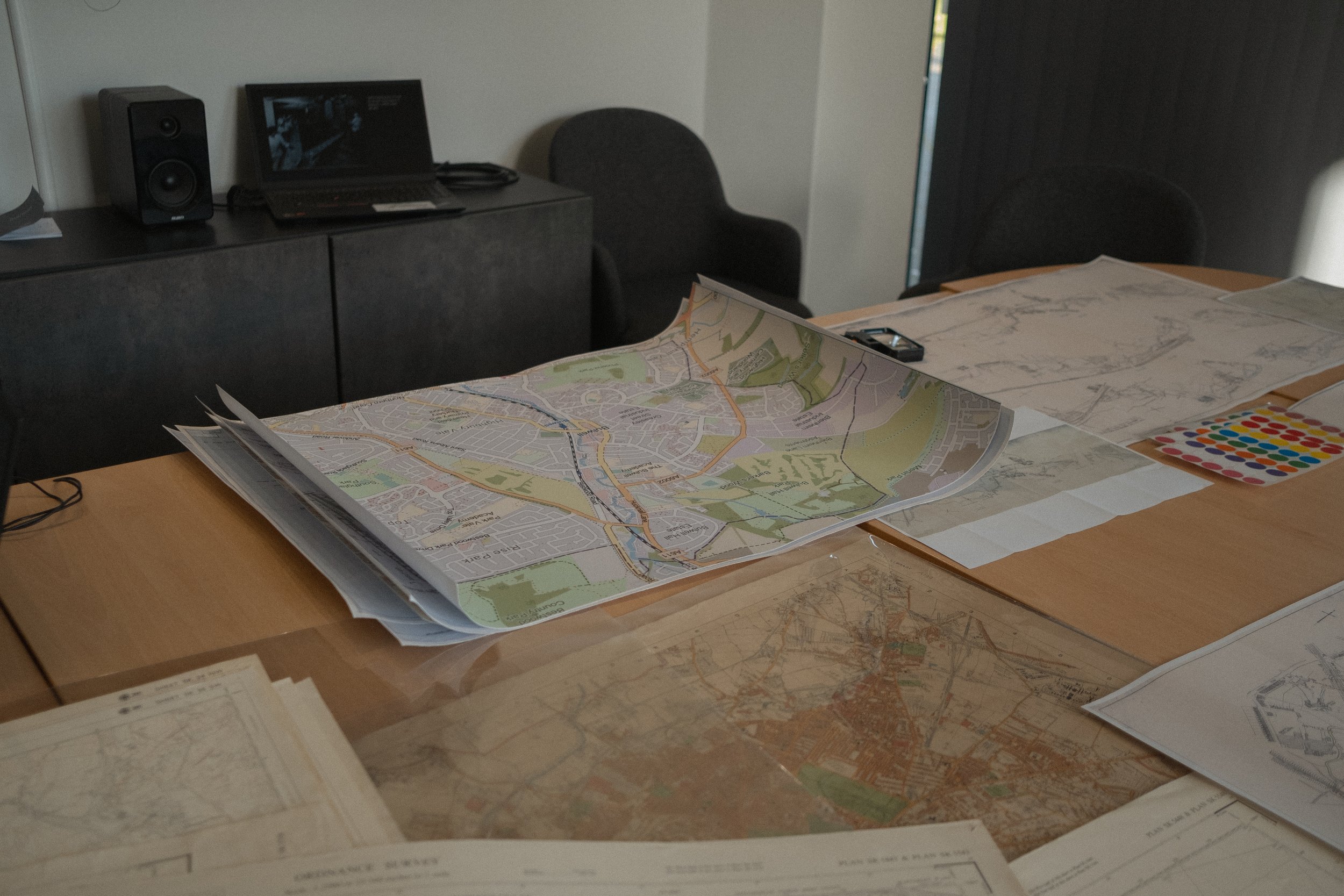

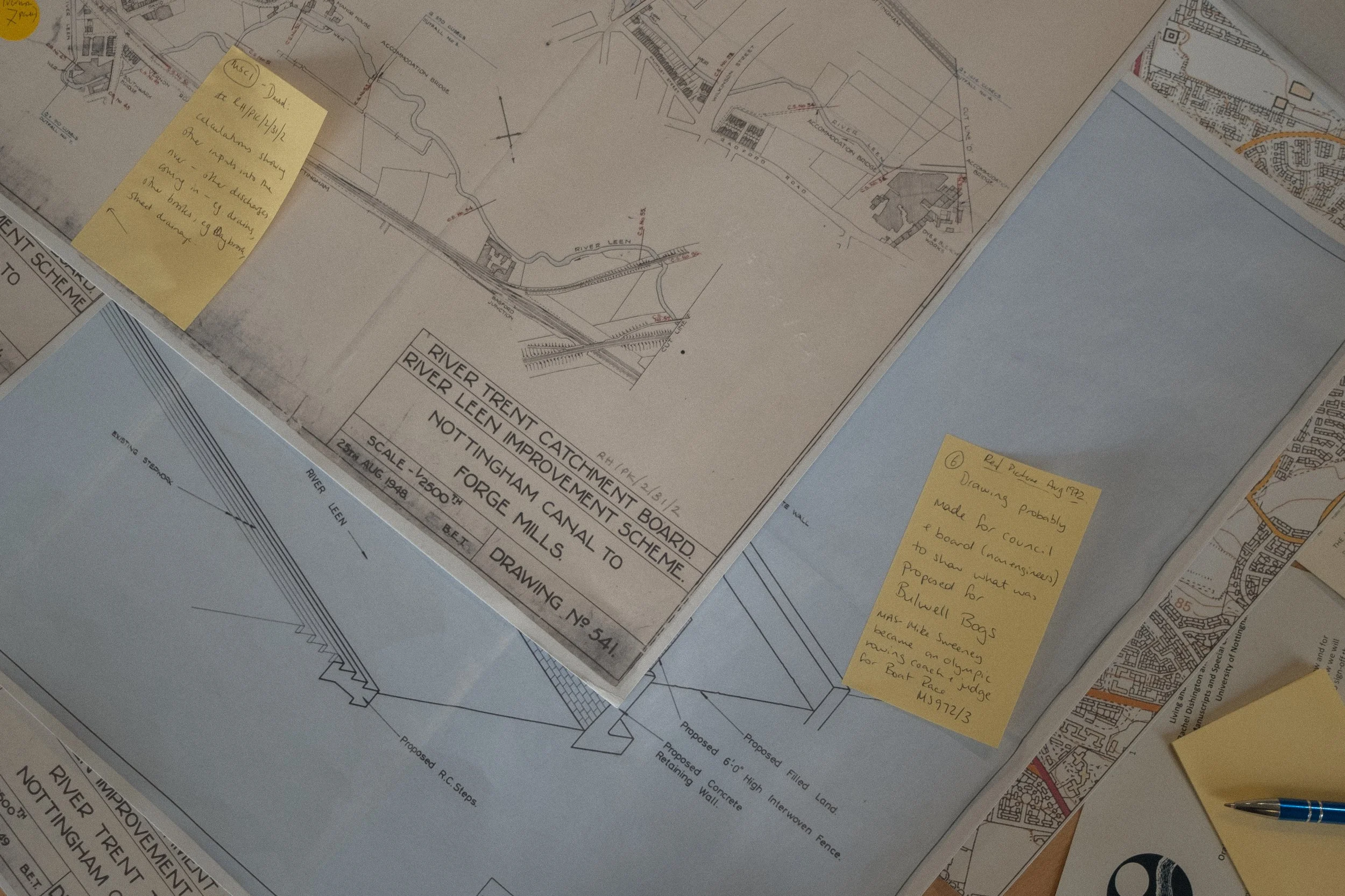

I walk through the café entrance and, after being momentarily lost, I see another volunteer sorting out badges; a strong sense of relief washes over me. I enter the room and my attention is immediately drawn to the maps strewn all over the table. What incredible details! The maps trace the course of the River Leen (the focus of this exhibition) through areas in Nottingham that one would least suspect.

The River Leen is not just a long tributary flowing through Nottinghamshire but old and historically rich, layered with centuries of English history. Over time the river has followed a series of radically altered routes, its architectural changes reflecting the tumultuous socio-political history of the county, particularly the city of Nottingham. Stretching 15 miles (24 km), the Leen is largely eclipsed by industrial and urban development, culverted and mostly inconspicuous to the public. It carves its way through Newstead Abbey, Bestwood Country Park, Bulwell, Basford, Lenton, the Nottingham Canal and The Meadows before joining its better-known counterpart, the River Trent. “I can’t believe how prominent this river is in Nottingham and how much history it has,” I mused as I walked around the small exhibition.

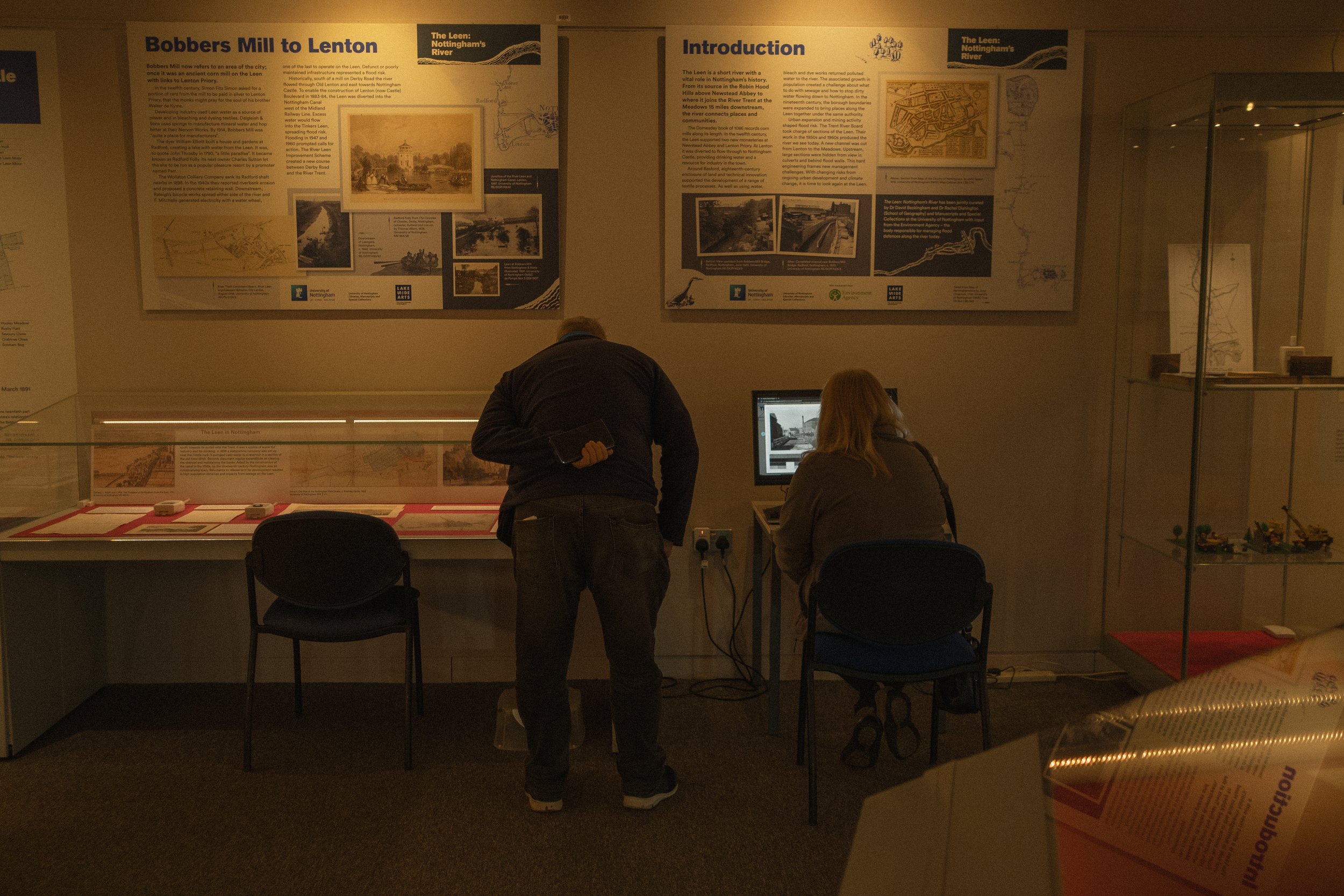

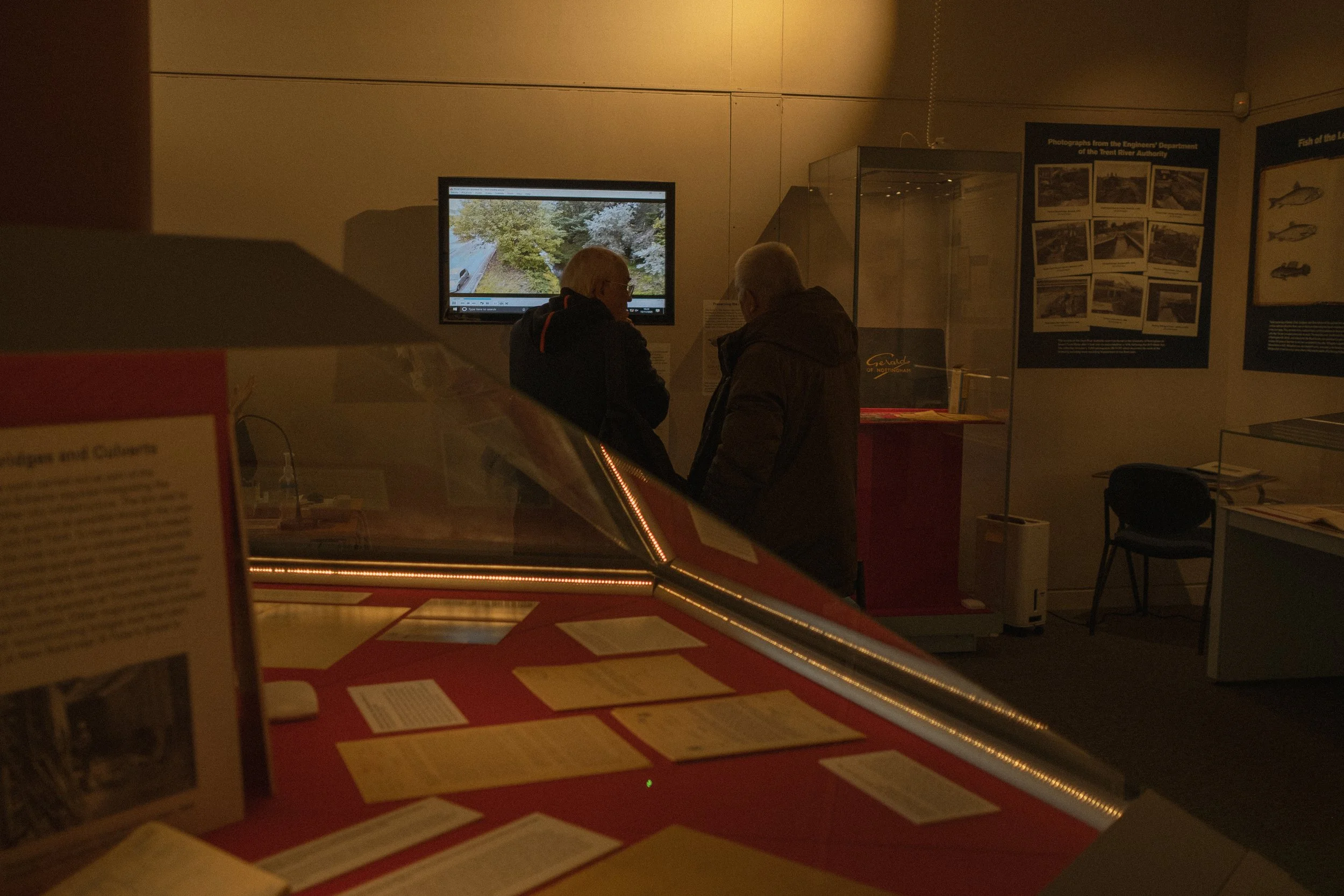

Throughout the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries the River Leen underwent a series of changes shaped by industrialisation and rapid urban growth. Early industrialisation altered its course, while later industrial expansion and the contamination of the river by sewage and industrial waste raised public health concerns, prompting reforms such as the Nottingham Borough Extension Act of 1877. Urbanisation also increased the risk of flooding, which severely affected homes and factories and ultimately led to the River Leen Improvement Scheme. Now, in the 21st century, the Leen is being re-examined as an overlooked river with cultural, ecological and social value. This exhibition can be seen as part of that re-examination, a chance for the people of Nottingham to pause and magnify the fleeting instances in their lives when the river has touched them, often without their awareness.

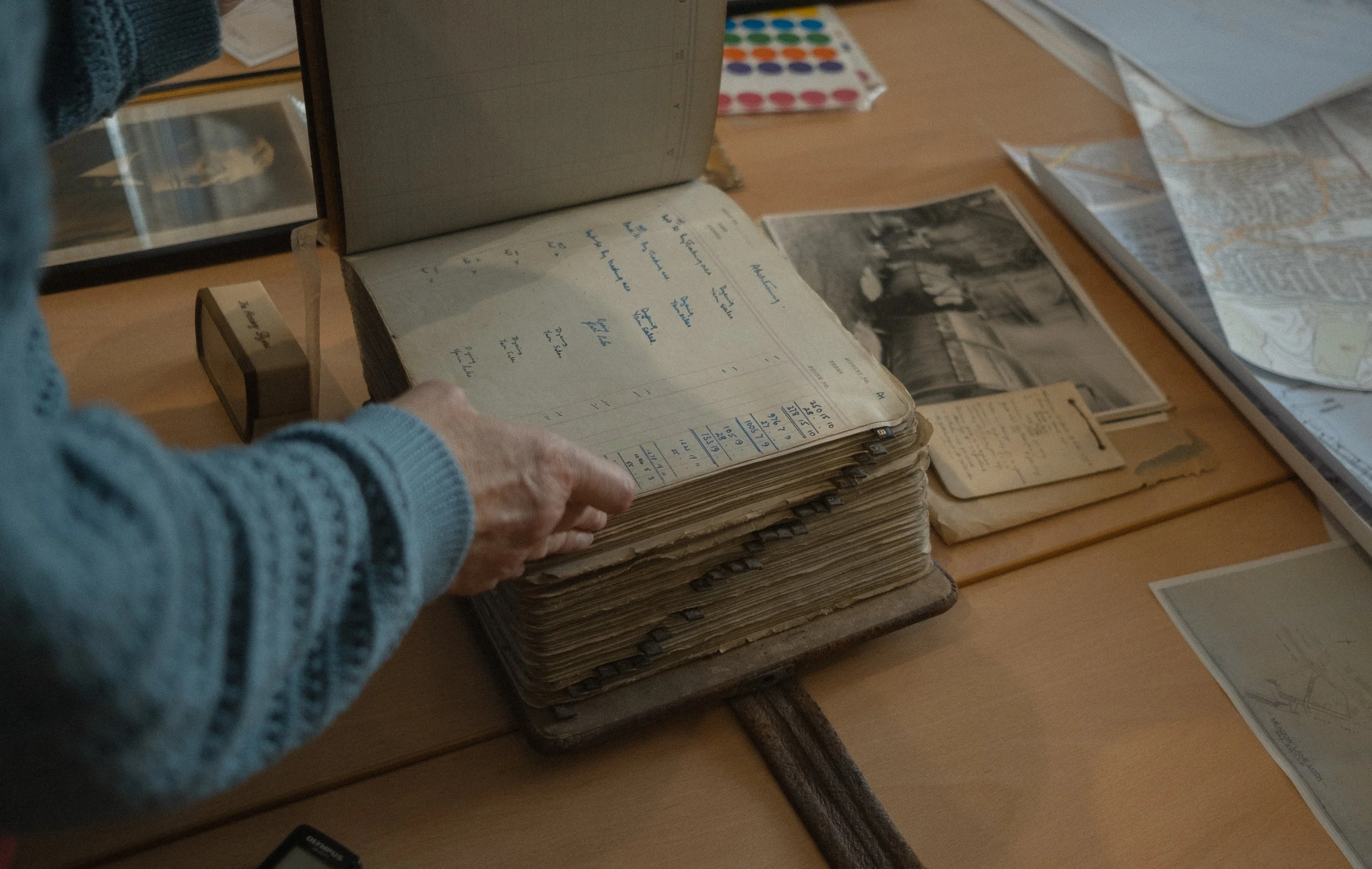

The maps were a vital tool for crowdsourcing information about the River Leen, for they not only document spatial data but also carry an affective significance, capable of triggering memories and personal associations. Treating maps as artefacts in this way represents a powerful approach for archival practice: they do not exist merely for functionality, but help us understand the dynamic relationships between places and humans. Jeanette Bastian observes how “maps and their innate recordness make the connections between archives and place clear and explicit,” providing mental and physical models that help “locating ourselves to ourselves, to one another, and to a global network.”² The affective significance of the maps became evident in their ability to evoke vivid emotional memories of the places connected to the River Leen, memories that seemed to have lain dormant for decades, yet awakened by the simple question, “What does the River Leen mean to you?” Using maps in this way, beyond their cartographic function, is crucial to appreciating the intertwining of historical data and lived experience. It becomes almost impossible to separate materiality from memory, as objects inevitably evoke passions, thoughts and emotions, whether sorrowful, painful or joyous. These maps left a profound impression on me, helping me understand how artefacts can be used in exhibitions not simply to inform, but to revive the past in the present.

After about ten minutes, once most of us had arrived, the exhibition slowly began, and already we had quite a few visitors. I noticed that there were far more older visitors than younger, which took me by surprise. One of the exhibition’s interactive elements encouraged visitors to write down their memories on post-it notes and then mark on the map where those memories had taken place. I found this a brilliant way to engage the public, allowing them to see how their personal histories were intertwined with the River Leen. I was even surprised to discover that the river ran beneath my old house, which prompted me to write my own post-it note, carving a small piece of my history into the exhibition. I had not previously considered post-it notes as artefacts, yet here they clearly functioned as a form of memory-making. Initially, I thought of what was unfolding as participatory archives, with the exhibition’s visitors actively contributing to and shaping the collective memory of the River Leen. As Ana Roeschley and Jeonghyun Kim note:

“Bridging the gap between the personal and the communal, community-based participatory archives allow community members to shape the archival record with documentation of their personal experiences and relationships. Through the contribution and preservation of personal items, community members exhibit both vulnerability and archival control.”³

Ordinary people are no longer merely passive witnesses to memory; they actively contribute to it by inserting their personal relationship with the River Leen into the archive. Any emotion, event, feeling, action or story (once transient and seemingly thrown in oblivion) is now situated within the River’s history, each moment cumulatively forming a fascinating piece of evidence not only of individual existence, but also of the socio-cultural significance the River Leen holds for its residents across generations. Yet, I find myself ambivalent about this supposed “archival control” that users have in such a context. While they can choose what to insert into the archive, I wonder how these contributions will be preserved and shared for future generations. Is sharing their stories enough? Should archivists offer participants more agency in determining how their stories are presented? The exhibition certainly exudes elements of participatory gestures though inviting the users to contribute their memories, yet the scope of this participation is still limited. This seems to be a common problem when it comes to institutional archives: this event was (and, it cannot be helped) time-bound, structured and organised by an institution. There felt like a tension between institutional control and participation, and I feel that this would be more pronounced later on when choosing how to present these newly shared historical data. Let’s consider Elizabeht Yakel’s questions: What level of participation provides sufficient mass to sustain a participatory archive? How do archives assess what is the most appropriate venue for participation around their collections?⁴ Public engagement was encouraged, but is that where it ends? I cannot help but admire the vigorous passion of individual archivists, who, as workers within institutional archives, endeavour to make ordinary people’s stories heard, yet even as I witness this engagement, the complex, hidden questions of authority and control continue to linger within the shadowed depths of my mind.

Despite these whispering reminders, there were moments of tenderness. One encounter that stayed with me was our interview with a middle-aged gentleman, the bubbliest and most heart-warming person I met that day. Speaking into the Dictaphone, he recalled how he once watched boys fishing in the river, a simple childhood scene now rendered impossible, the fish having long since died. The vitality surrounding the river vanished, leaving a quiet sadness associated with his memory. It is precisely these acts of engagement, this process of creating alongside the community, that give my work as an archivist its deepest sense of meaning. One is no longer merely analysing artefacts already established and fixed in time, but actively participating in the making, witnessing and understanding of history as it unfolds.

Yet, when asked if I wanted to conduct the interviews, I hesitated. My uncertainty was not shyness but a quieter question of authority: who was I to ask, when I felt I did not yet know the river? I felt unprepared, nervous and acutely self-conscious of my role, my heart fluttering and my palms on the verge of sweating. I wondered whether this anxiety stemmed from a heightened sense of responsibility, a fear of disrupting or mishandling the delicate process of creating and curating memory in real time. The emotions I experienced felt foreign, questions rushing in faster than answers could form, as though I were sinking into quicksand. I simply did not know what to ask, my limited knowledge of the River Leen leaving me without the framework of prepared questions.

In more formalised oral history interviews, I am accustomed to structure: planned questions, contextual knowledge and the confidence that comes from knowing how to follow a narrative thread. This encounter, by contrast, felt too informal, too abrupt. This sense of unpreparedness and the reluctance to fail speaks directly to the ethical tensions embedded within oral history practice. Alessandro Portelli argues that oral history is not defined by neutrality or expertise but is instead permeated by uncertainty, subjectivity and uneven power relations between interviewer and narrator.⁵ Seen through this lens, my emotional discomfort begins to make sense. Occupying the role of an ‘authority’ figure while simultaneously feeling uncertain, under-informed and hesitant rendered that authority unstable. Some oral historians see instability not as a flaw, but an intrinsic condition of oral history, resisting the notion that the interviewer must know in advance. Yet my own experience suggests otherwise. While I am drawn to the idea of oral history as conversation, as a space where stories unfold organically, I remain convinced that structure and preparedness are not diametric to intimacy. My hesitation reflects this unresolved tension: an uncertainty about where my responsibility lies and how best to balance openness with accountability in the act of listening.

And so, as I left the busy room, animated by jovial discussions, interviews and new introductions, I felt content that the event had provoked such interest, yet quietly disappointed in my own lack of confidence when it came to fully engaging with the visitors. Still, I did my best. And so, as M. Legrandin advises, “always try to keep a piece of sky over your life.” The experience was challenging, yet it offered a certain freedom of action, thought and emotion: the freedom to learn through jitteriness, reluctance and hesitation, and to understand more clearly where those emotions originated. What, then, is an artist’s nature and how does one guarantee it is never stripped of what it needs? Perhaps it lies in a heightened sensitivity, a willingness to be consumed by curiosity and an acute awareness in observation. I would like to think that, in my own way, I embodied these qualities during my time helping with this exhibition.

¹ Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time: Volume 1, trans. Lydia Davis, ed. Christopher Prendergast (London: Penguin, 2002), pp. 70–71.

² J.A. Bastian, Records, Memory and Space: Locating Archives in the Landscape, Public History Review, 21 (2014), pp. xx–xx. Available at: https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/phrj/article/download/3822/4604 (Accessed: 3 February 2026).

³ Ana Roeschley and Jeonghyun Kim, “‘Something That Feels like a Community’: The Role of Personal Stories in Building Community-Based Participatory Archives,” Archival Science, 19, no. 1 (2019), p. 28. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-019-09302-2 (Accessed: 3 February 2026).

⁴ Elizabeth Yakel, “Who Represents the Past? Archives, Records, and the Social Web,” in Controlling the Past: Documenting Society and Institutions—Essays in Honor of Helen Willa Samuels, ed. Terry Cook (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2011), pp. 257–278.

⁵ Alessandro Portelli, The Death of Luigi Trastulli and Other Stories: Form and Meaning in Oral History (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1991), p. 50. Available at: https://archive.org/details/deathofluigitras0000port/page/50/mode/2up?q=subjectivity (Accessed: 3 February 2026).